For a prolific Syrian restaurateur, rebuilding a business as a refugee took life-threatening risks, lots of time, and nights spent sleeping on the doorstep of a church in France.

Imad Alarnab owned three restaurants, five juice bars, and a number of coffee shops in his hometown of Damascus. But in the summer of 2015, after his restaurants were destroyed amidst the worsening violence of Syria’s ongoing civil war, he was forced to flee the country.

“I went through Lebanon, then Turkey, Greece, Macedonia, Serbia, Hungary, Austria, Germany, France, and then the U.K.,” Imad tells me. It’s a route that many refugees followed that summer as their numbers dramatically increased, leading to the declaration of a migration crisis in Europe. That route has since closed, with the borders of multiple countries sealed off, leaving many refugees stranded in poor conditions in Greece. Imad was lucky. “Crossing borders, it wasn’t me; I felt guilty every time I was doing it,” he says. “I couldn’t have imagined myself doing something like that, but I had to.”

Imad’s second-to-last stop on his journey was Calais, where he spent 64 days before finally making it to the United Kingdom. The small port town in northern France is the site of the Channel Tunnel, the undersea rail tunnel connecting France and Great Britain. Over the years, a number of refugee camps have sprung up in Calais as refugees hoping to cross the channel illegally have made their way to the city, with most using the camp as a staging ground for their attempts to clandestinely cross into the U.K., attempts that can all too often prove fatal.

When I visited for a few days of volunteering in 2016, a year after Imad was there, I stayed in a shanty town of about 10,000 people, the infamous Calais “Jungle,” which has since been dismantled by French authorities. The camp lacked basic facilities, and conditions were disturbingly harsh, but the people living there were unbelievably generous with their resources and skills. It was the food I ate there that left the greatest mark on me—the teeth-achingly sweet tea, perfectly crisp flatbreads, Sudanese rice dishes, and the best shakshuka of my life. These meals made the human cost of the refugee crisis feel tangibly real to me.

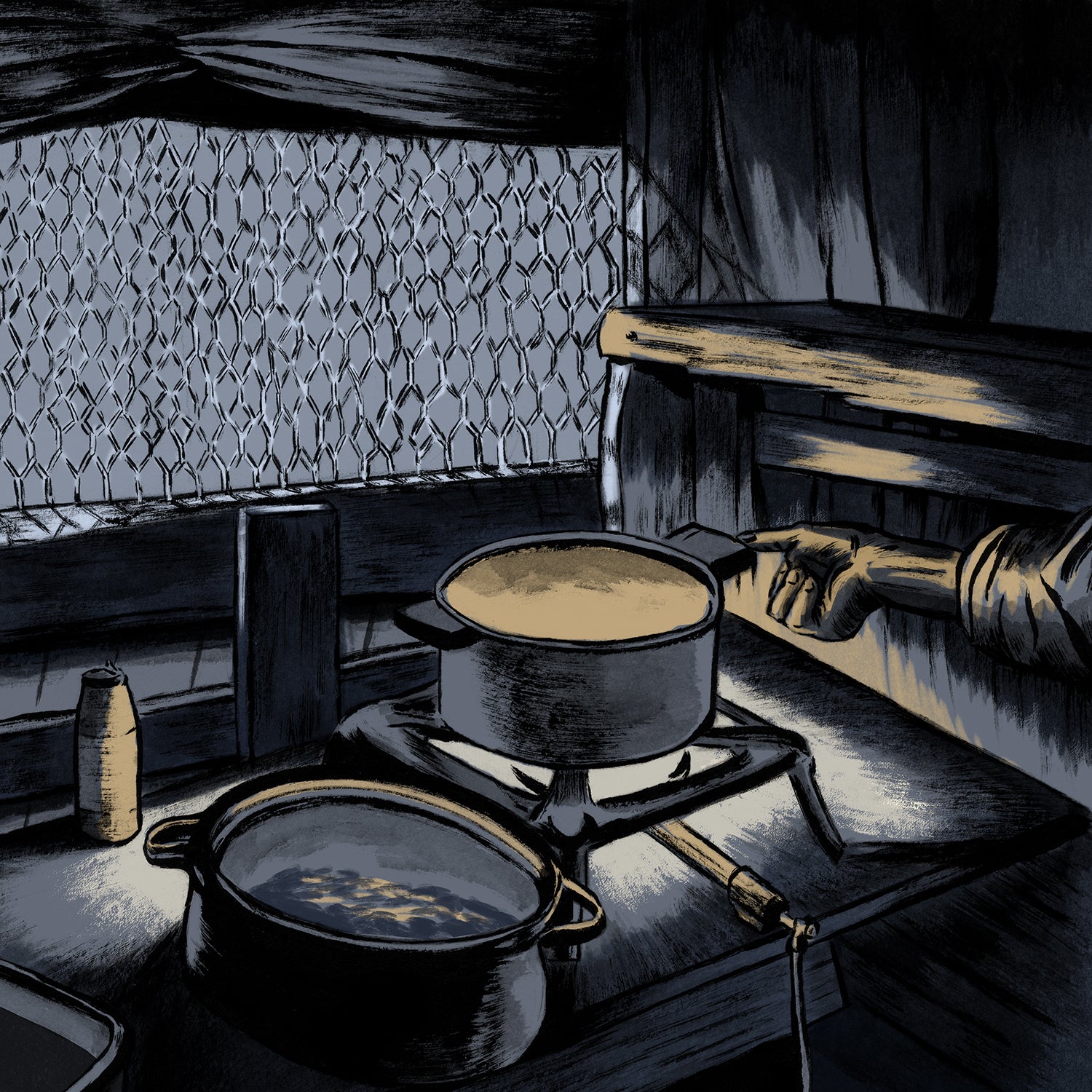

In Calais, Imad slept on the steps of a church in the center of town and used a donated stove to cook for scores of other refugees. “It was difficult sleeping on the steps of the church; sometimes it was windy, or it was raining or cold,” he says. “But it was also beautiful because I was meeting a new friend every day.”

Imad is now living in London, where after a brief stint as a car salesman, he is back to doing what he does best: masterfully cooking the food of Damascus. At Imad’s Syrian Kitchen, his aptly named pop-up restaurant at 134 Columbia Road in Bethnal Green, he has partnered with the U.K.-based humanitarian organization Help Refugees to donate his proceeds to Hope Hospital, a children’s hospital in Aleppo that serves a community of 250,000 people.

The restaurant is located in East London, above Columbia Road’s bustling flower market. Everything is served on communal platters, and diners eat at narrow tables, elbow to elbow. The menu includes succulent grilled chicken, falafel that is shatteringly crisp on the outside and impossibly fluffy on the inside, and the smokiest babaganoush I’ve ever tasted.

In person, Imad is warm and gregarious, and he seems genuinely touched every time he receives a compliment for his cooking, something that happens often during the brief time I spend with him. His mother taught him how to cook, and most of the recipes Imad uses are hers. “What I’m trying to do here is serve traditional homemade Syrian cooking, and when I say homemade, I mean honestly made in the home,” Imad says.

“We wanted to create something positive amid the chaos by working with Imad,” says Tom Steadman, Help Refugees’ head of communications. “A place where the public can see refugees contributing to the culture of Britain, and at the same time give people a simple, practical way to help those most in need.”

Besides Imad’s restaurant, supper clubs, catering businesses, food classes, and restaurants have been set up throughout Europe by, and employing, recently arrived refugees. In Germany, the charity Ber den Tellerend connects local Berliners and refugees for cooking classes held in an informal setting where students learn to prepare a dish from the home country of their refugee teacher. In Brussels, the Syrian-owned catering business We Exist helps refugees gain access to the labor market and organizes Syrian cooking classes.

Attitudes toward refugees are highly polarized in Europe, and anti-migrant sentiment in Europe has propelled far-right political parties to positions of power and increasing influence across the continent. The number of refugees arriving in 2018 is far below the peak of 2015, but the policies implemented to dissuade them are becoming more brutal and inhumane.

One of the most disturbing examples is Italy’s new far-right interior minister, Matteo Salvini, barring NGO ships from rescuing adrift refugees in the Mediterranean, leading to hundreds drowning in recent weeks. Death on this scale has become an accepted, and easily ignored, everyday reality in Europe. It’s why initiatives like Imad’s Syrian Kitchen are so very necessary. Food won’t solve these issues, but reminders of our common humanity are sorely needed in today’s Europe.

Food doesn’t just preach to the converted, either. As I leave Imad’s restaurant, he tells me about an unlikely friend he made in Calais. “He was one of the far right, and he was against everything to do with immigrants,” Imad says. “One day we were fishing, and we caught some nice fish, and we asked him to try one of them, and he asked about the recipe. And then little by little, we kept talking about what’s happening in the world, and then he was interested to know the true story about Syria, and since then we are friends.” That friend, Imad adds, just came to visit him in London.

To visit Imad’s Syrian Kitchen, or to donate to Help Refugees, follow this link.