A Mexican chef turns an obtuse cookbook author into a salsa-making machine.

Ten years ago, I was a young writer who thought eating tacos in the back of a New York City bodega and completing a comprehensive tour of San Francisco’s best burritos represented the height of culinary understanding. Then a friend suggested I meet the chef Roberto Santibañez to discuss helping him with a cookbook. Arrogant and ignorant, I was underwhelmed by the prospect of working on a Mexican cookbook: Tacos, beans, and that chocolaty mole—it was all good, if a bit uninspiring. And believe me, I knew what I was talking about. After all, I had been to San Miguel de Allende, for chrissakes.

Had I been more curious, had I flipped through even one cookbook by someone like Patricia Quintana, Zarela Martinez, Diana Kennedy, or Rick Bayless, I might have understood that Mexican cuisine is as rich, varied, and sophisticated as Chinese, Indian, French and Italian. But for better or worse, it took a generous, barrel-chested native of Mexico City to show me how little I knew about so much.

I took the meeting, albeit grudgingly. When we met at Roberto’s Manhattan apartment, I was immediately taken by his enthusiasm. He seemed exhilarated when I betrayed my ignorance of the food of his home country in the same way I get excited when I hear that a friend has never watched Twin Peaks. He knew I was in for a treat. Ultimately, my naiveté about his food and culture was a big part of what convinced him to hire me—I was his target audience.

He told me about his life and how it had informed the book he now wanted to write. He had first learned to cook by watching his grandmother and aunts roast tomatillos and toast chipotles on a flat pan called a comal in their Mexico City kitchens. After high school, he spent two years at Le Cordon Bleu in Paris, studying the French mother sauces and their kin. Afterward, he returned to Mexico City, where he opened a series of progressive restaurants and began to wonder why Mexico’s sauces shouldn’t be similarly codified. He eventually moved to the U.S., helming the kitchen at storied Fonda San Miguel in Austin and later serving as culinary director for the ritzy Mexican restaurant group Rosa Mexicano. When he left in 2009 to open his own restaurant, Fonda in Brooklyn (which now has two branches in Manhattan), he decided to turn the idea that had been bubbling for decades into a book: essentially, a treatise on Mexican sauce-making.

The first chapter, he said, would be focused on salsas, and for the life of me, I couldn’t imagine how three recipes could fill a whole chapter. Because as everyone knows, there are just three salsas: red, green, and pico de gallo. Once we got started, of course, the problem of filling pages quickly gave way to the agonizing task of winnowing down a seemingly endless list—peanuts fried and blended with dried chiles de árbol, slightly funky seeds from guaje pods pounded with jalapeño and cilantro, charred onion and serrano chiles chopped and seasoned with lime juice and Worchestershire—so the book didn’t become a 400-page salsa manifesto.

In the subsequent months, I watched him make dozens of these fiercely spicy, lip-smackingly tart, and insistently salty sauces. Far too intense, by the way, to eat with Tostitos Scoops. In Mexico, salsas aren’t typically intended for chips, though as Roberto reminded me, they can be applied to virtually anything that would benefit from their electricity—rice and beans, meat and fish, soups and sandwiches, tacos and quesadillas, tlacoyos and tlayudas.

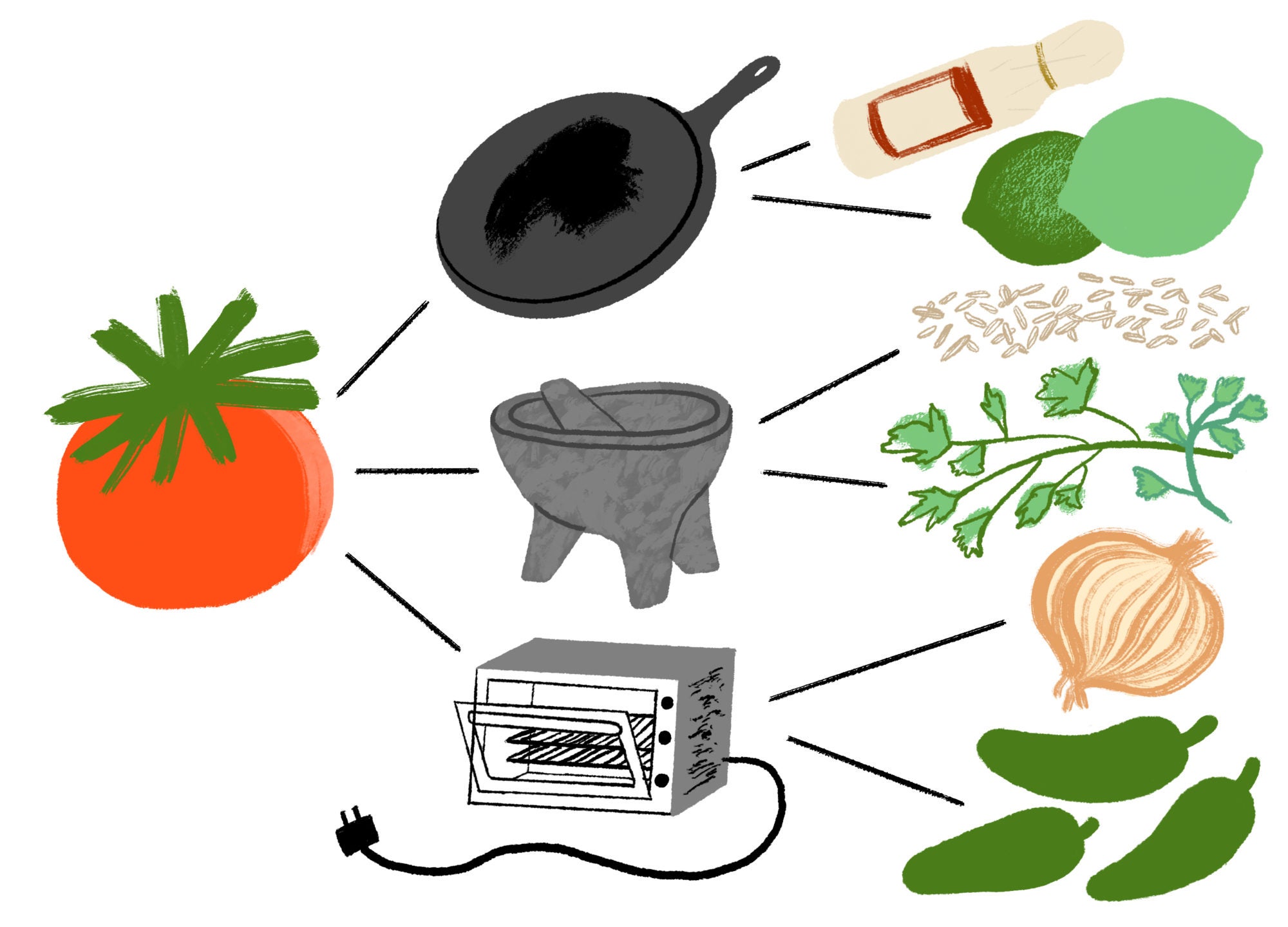

While Roberto taught me that this category of sauces is so varied that it defies generalization, he also understood that for the novice, a little oversimplification could provide much-needed encouragement. So he provided a rough formula: Basically, Fruit or Vegetable + Chile = Salsa. The fruit or vegetable (often tomatoes or tomatillos but by no means limited to them) might be raw or cooked, chopped or blended or ground in a volcanic-stone mortar called a molcajete. There is usually plenty of acidity, either from the fruit itself or in the, say, lime juice or vinegar you add, and plenty of salt, too. Often, complementary ingredients like cilantro, onion, garlic, and spices like pepper and cumin join the fun.

I watched him make dozens of these fiercely spicy, lip-smackingly tart, and insistently salty sauces. Far too intense, by the way, to eat with Tostitos Scoops.

I imagine he had higher aspirations for his book—ultimately called Truly Mexican—than turning a hipster schlub like myself into a superstar among his dinner guests. Yet I can attest that he achieved that much, at least. With a general blueprint in place, the vast cosmos of salsas suddenly seemed cookable. And so the same home cook who can’t be bothered to make stock and who buys rice from the Chinese takeout place on his corner instead of mixing water and raw grains in an electric cooker found that salsas had become part of his weeknight repertoire.

This is because, at the risk of sounding like the chefs at whom I like to poke fun, making salsas is easy. And not in the way roasting chicken is easy, but actually easy. They also make cooking something delicious for dinner easy, since a few spoonfuls will turn even your simplest, dullest, chicken-breast-on-brown-rice-est dinners into a thrill.

I came away from the project not only with a roster of great salsas, but also with something unheard of in my kitchen: the confidence to improvise.

Whenever I want to make salsa, I follow a sort of culinary decision tree. I can keep the fruit raw or roast it (in my toaster oven, Roberto’s sneaky subtitute for the comal), without oil and until it chars, so it develops a subtle bitter edge. I can add fresh chile (jalapeño, serrano, habanero, etc.) and leave it raw so it’s sharp and vegetal, or I can roast it so it gets sweeter and more interesting. Or I can choose a dried chile (such as the nutty árbol or smoky chipotle) and toast it in a dry pan until it’s especially fragrant. Chopped or blended together and seasoned aggressively, the resulting concoction is salsa. And thanks mostly but, incredibly, not entirely to Roberto, it tastes so good I can hardly believe I made it myself.