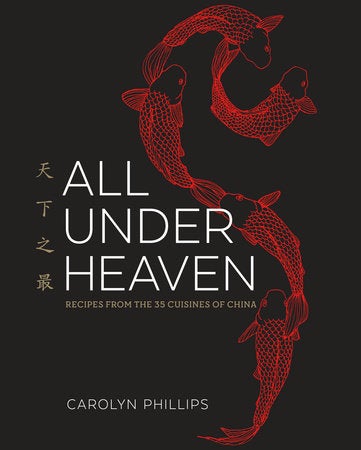

Carolyn Phillips’s exhaustive study of Chinese food culture is a thing of legend. Nearly 30 years ago, Phillips married into a Chinese family and—while mastering the language—fell hard for the country’s regional cuisine, including dim sum (more on that later). In her dense and exhaustively researched new book, All Under Heaven (Ten Speed Press), Phillips dives into the eight traditional “great cuisines” established during the Qing dynasty (1644–1911), which include some familiar regional cuisines, such as Hunan, Fujian and Sichuan. Each of the 300 recipes features a detailed headnote, and the author’s pencil illustrations tell the story visually—in a sort of Wall Street Journal meets Lucky Peach way.

But it was during her travels as a Mandarin interpreter that Phillips realized the country offered many other lesser-known micro-cuisines, like in the northeast, where the populist Han cooking style blends with Muslim, Mongolian and Manchurian traditions. Halfway through the 500-page doorstop, a chapter covers the sparsely populated “arid lands” of Gansu, Xinjiang and the Gobi Desert region of Inner Mongolia. The cooking, with origins in the populated eastern metropolises, is almost unrecognizable from what many perceive as Chinese Cuisine™—including a cumin-rubbed beef, ginger, and cilantro dish called silk road fajitas. However, in the chapter there’s also a crack recipe for the familiar Lanzhou beef noodle soup, which has become a staple on the restaurant scene in NYC and Los Angeles.

And then there is dim sum, a teahouse tradition in China that has been reinterpreted as a brunch or lunch activity in the United States. Dim sum is—as a whole—small plates of dumplings, noodles, cakes and sweet things circulated on trolley carts. The eating process can be fast and furious. The diner points, and the server delivers while marking off a communal tally card in the process. Phillips is a big fan of dim sum, and in conjunction with All Under Heaven she has published a pocket-sized guidebook, the Dim Sum Field Guide. In the slim book, modeled slightly after the Audubon Society birding guides (spotting dumplings and rice wrappers in the wild, get it?), she includes descriptions of variations on popular dishes like siu mai, xiaolongbao, char siu, and sweets like milk tarts and black sesame rolls. If you don’t know dim sum that well, this is the primer you were in search of—and flipping through the 80 pages offers a smart look at the scope of this wonderful style of eating. It was a difficult task to pick our five favorite dim sum dishes, but here they are nonetheless.

1. XIAOLONGBAO

IDENTIFICATION Named after the “little baskets” in which they appear, these Yangtze-style morsels (sometimes called “soup dumplings”) always contain a good amount of jelled stock that melts as the meat filling steams. The most elegant examples of this genus are enclosed in paper-thin pasta dough made with hot water, which gives the surface an extraordinary tensile nature. Pick these up by their topknot with your chopsticks and immediately cradle them in a spoon, as they should ideally be filled with searing hot juice. The exterior is smooth and tacky; the interior is tensile and soupy. Sometimes referred to as “XLB” in English.

BASIC FILLING Minced pork, jelled stock, and seasoning.

DEFAULT SAUCE OR DIP Dark rice vinegar and thin shards of young ginger.

NESTING HABITS Four or so are clustered inside a bamboo steamer basket, and nowadays they’re often nestled in small foil cups to help prevent them from tearing.

ORIGINS One of the few non-Cantonese tea snacks to slide fairly recently into the dim sum hierarchy, xiaolongbao are natives of Jiangsu.

2. CHAR SIU BUNS

IDENTIFICATION Springy, with a yeasty aroma, these baozi (filled and stuffed steamed buns) are wrapped with a special Cantonese dim sum bread dough so as to make the dough splay open into three or so shiny white “petals” that are craggy along the edges. The mahogany filling of chopped char siu in a sweet sauce is visible between the petals. Often sold in Chinese bakeries, as well as in just about any dim sum teahouse, the buns are protected by little paper squares on the bottom to keep them from sticking to the steamer. The exterior is fluffy with a smooth surface; the interior is soft with chewy bits. Also called barbecue pork buns, even though the pork never comes near an actual barbecue.

BASIC FILLING Char siu seasoned with a light, sweet gravy of soy sauce, shallots, sugar, oyster sauce, hoisin sauce, and sesame oil.

NESTING HABITS Often found in clusters of three or four in a medium-size bamboo steamer basket, although larger ones may nest alone in smaller baskets atop waxed paper squares; these bigger ones can often be sighted in Chinese bakeries.

ORIGINS This bread dough is light, fluffy, and tensile, due to its assorted leavening agents. Cantonese baozi were first sold as snacks in Guangzhou teahouses. The classic description is “high in body with the shape of a sparrow’s cage, a big belly that is firmly gathered up [at the top], and a mouth that explodes to ever-so-slightly reveal the filling.”

3. HAR GOW

IDENTIFICATION Multiple delicate folds on one side only give this delicacy its unique shape. It traditionally has 12 folds and a fat purse shape that Chinese gourmands have described as a “spider’s belly.” The bright pink color showing through the vaguely sticky and shiny exterior demonstrates why these divine dumplings truly deserve their Chinese name, “shrimp jiaozi.” A celebration of the exquisite quality of perfectly fresh shrimp, har gow are extraordinary when done right because there is simply no place for mediocre ingredients to hide. The exterior is dry and slightly tacky to the touch; the interior is very crunchy and luscious.

BASIC FILLING Pure chunks of fresh shrimp jumbled with tiny bits of pork fat and bamboo shoots.

DEFAULT SAUCE OR DIP If you like, dab these very lightly in a mixture of mustard and soy sauce.

NESTING HABITS Usually found in clusters of four closely nestled together, but never touching, in a small steamer.

ORIGINS The wrappers are most likely a spin on the wheat-starch wrappers of Fun Gor. However, the filling was the inspired creation almost 100 years ago of the Yizhen Teahouse. Located on a tributary to the Pearl River, the chef at this famed eatery used the traditional culinary concept of seasonal dining to develop these extraordinary morsels out of the day’s freshest catch.

4. GARLIC CHIVE PACKETS

IDENTIFICATION Translucent balls stuffed with finely chopped garlic chives and the occasional fresh shrimp are pan-fried on both sides to create a light golden crust. The Chinese variety of chives is flat and much wider than its Western counterpart, is much more like a true vegetable, and possesses the warm aroma of fresh garlic. The wrappers are made out of sweet potato flour and wheat starch mixed with boiling water, and this gives the packets a snappy texture. Sweet potato flour is a signature ingredient of a delectable trifecta in China’s cuisines: the region surrounding the southern edge of Fujian, northeastern Guangdong, and the inland hill country. This is where the foods of Chaozhou, the Hakka, and Southern Fujian have intertwined for centuries. The exterior is dry and tacky, with the fried areas slightly crisp; the interior is juicy and very flavorful.

BASIC FILLING Chopped garlic chives seasoned with salt, pepper, and a touch of oil to provide a buttery texture against the stark cleanliness of the vegetable. Diced fresh shrimp are often added to create a sweet, pink contrast to the aromatic emerald chives.

NESTING HABITS Three on a plate, often arranged on a doily or shredded lettuce.

ORIGINS Garlic chive packets are members of the enormous group of steamed or pan-fried foods called guo that are popular throughout Southern Fujian, Hakka areas, Chaozhou, and wherever the Chinese diaspora has set down roots, such as in many parts of Southeast Asia. Guo are also made from ground sticky rice, or sometimes from wheat starch, and may be filled.

5. CUSTARD TARTS

IDENTIFICATION Tartlets of Chinese puff or short pastry hold puddles of sweet, quivery custard. Terrific when freshly made and still a bit hot, these tarts can also be enjoyed warm or cool, and each one usually serves a single diner, although you can ask that they be cut in half. The top surface ought to be as shiny as a mirror, and the custard should be a deep lemon yellow with the faint aroma of vanilla. Exterior is crisp and flaky; interior is soft, gently sweet, and eggy.

BASIC FILLING Eggs, milk, sugar, and vanilla.

NESTING HABITS Three hovering together in small foil cups on a plate; often available in Chinese bakeries.

ORIGINS Custard tarts are, in all likelihood, a Guangzhou interpretation of the English custard pie as small, open-faced tartlets. Others insist that these are interpretations of pasteis de nata, but as Guangzhou and Hong Kong have traditionally served unbrowned custard pies, and since these have been part of British cuisine for at least 700 years, custard tarts probably are direct descendants of the same sweets once enjoyed by Henry the Eighth. They became popular in Guangzhou during the 1920s, when department stores hired chefs to cook special treats like these to lure in customers from their competitors.

Reprinted with permission from The Dim Sum Field Guide by Carolyn Phillips,copyright © 2016. Published by Ten Speed Press, an imprint of Penguin Random HouseLLC. Illustration credit: Carolyn Phillips © 2016