Or, how I learned to break free from heat maps and tyranny of trendy

Blink, and you’ll miss the best restaurant in town. It’s a diner under a freeway ramp, next to a wine warehouse, where the waiter looks worried when I tell him my doctor’s nixed bread. He instantly shifts into problem-solving mode, bringing out my “usual”—a plate of eggs Benedict, with that thick cut of country ham—over a bed of hash browns instead of an English muffin. I return twice a week for, presumably, the rest of my life. I try to keep the place to myself, but it’s so perfect, with its reliable essentials and its cheap diner mugs of coffee, that I invite a friend for breakfast one day and swear her to secrecy.

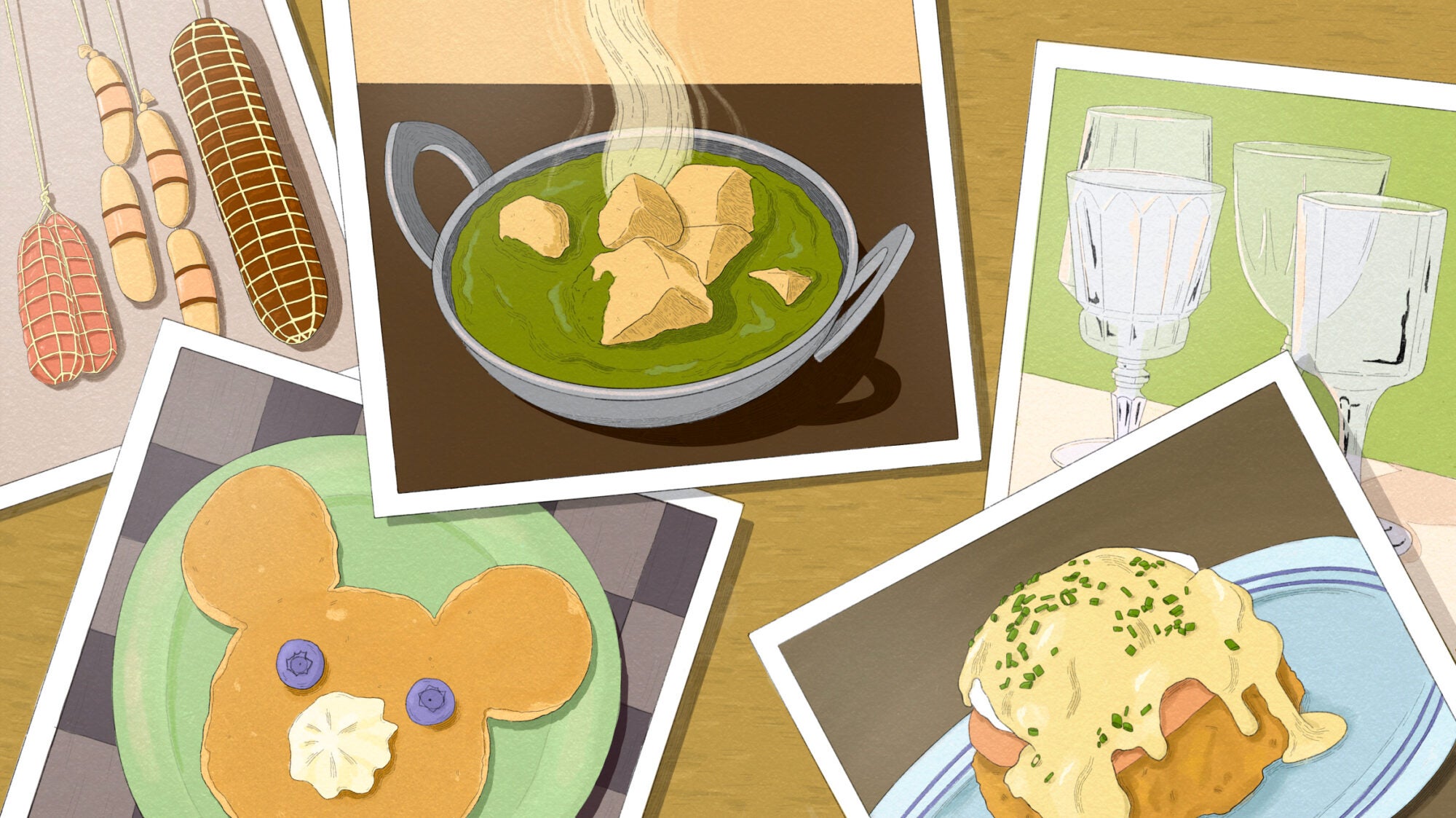

This circle of trust widens when I take my kids there to try a Mickey Mouse–shaped pancake. He has a berry-lined face and a nose made of Reddi-wip. “You’re here all the time?” they ask in unison, looking around, incredulous, and I nod. “How did you find it??” I tell them I passed by once after school drop-off, and I liked the name, so I went in. It’s not the worst for them to learn I have a life—one in which I can step back from caretaking and I’m casually brought a side of hollandaise sauce with anything I order, even if I forget to ask.

At the best restaurant in town, reservations are easily available, because people aren’t elbowing each other out of the way in a quixotic tilt at self-worth. I was originally mailed a flyer for this nondescript Indian place owned by a smiling Punjabi man whose kids work there as well. The food is so good that I can look the other way on the accommodations they’ve made to reel in what they believe is a hipper crowd: a few sticky specialty cocktails, fusion-y appetizers like an unnecessary papadam bruschetta and mac-and-cheese samosas. I don’t have the heart to tell them that their appeal lies in their profound and effortless dorkiness.

The owner lingers by the table, pretending to wipe something down while I start to eat my saag paneer. It reminds me of my mother’s silent observations when she’s feeding me at home: he’s waiting to see if I’m enjoying my meal, and I am. They’ve taken the time to soften and pan-fry the paneer before stirring it in, and the silky texture of the bright green saag hasn’t been cheated with cream. I make loud, appreciative noises, and he walks back to the kitchen, satisfied. I find a family member to thank on the way out.

Blink, and you’ll miss the best restaurant in town.

The best restaurant in town is an Italian grocer in a neighborhood with mushy borders, where the owner lets me try three kinds of ham and a bunch of cheeses before I have to decide on anything. We discuss at length the signs he hangs all over the place. “This sonofabitch is mine; don’t tell me how to run it!” says the one near the register, and I agree with the sentiment, although I tease him: everyone who works there is a softy. Yeah, well, you should see the dummies who come in sometimes, he grumbles. I take this as a veiled compliment. I say he should send them to that other Italian grocer—you know the one—and he chuckles. I don’t share that I found him when I was specifically looking for an Italian grocer and scrolled past the famous ones, the ones who know how to optimize their searchability.

I may have a soft spot for purveyors who are better at their craft than at the internet. I point at another sign that says, “Your husband called, he says you can buy anything you want.” That one needs an update, I tell him. Women make their own money now. He mulls it over. “What is it, ‘partner’? Maybe we change it to ‘spouse.’” “Maybe it’s a nice sign about gifting,” says his wife, from over near a vat of simmering pork meatballs. She’s preparing for the lunch rush, a long line of off-duty firefighters. She shoots him a pointed look. “I like to receive gifts from you,” she says. “I like to receive them too,” he says. “So where does that leave us?” It leaves me overly involved in their personal and professional endeavors, but these are the moments that keep me looking for food outside my own home.

Because slinging myself between work and kids and our two proscribed units of fun every week can shrink-wrap our lives, and I often feel my zone of comfort narrow with it. Suddenly, everyone we know plans their fun units by consulting the same three food maps, grumbling about not wanting to waste a meal. And with the rising costs of dining out, taking a chance on something new or untested can also mean a significant financial hit. But the best restaurant in town reminds us that we weren’t meant to travel through the world like it’s a listicle-driven scavenger hunt.

We are meant to travel through it porous, full of curiosity, inviting serendipity and connection. We are meant to crave Burmese food on a Tuesday and see that craving through with a thorough internet search that leads us to a scrappy young woman with a pop-up. She posts on Instagram one day saying she has to fold and is selling all of her leftover bags of fermented tea leaves. She says that they freeze well, and I tell her I want them for homemade lahpet thoke, but we talk logistics, and it turns out I can’t make it across the city in time.

She hasn’t posted about her own food in a year, but she seems to be doing well otherwise. I think about her all the time, as rents skyrocket and food service margins fall. I’m still so invested in her well-being that I hope, even though all the financial data tells me otherwise, that she’s quietly gathering cash for a storefront, because she, of all people, deserves it.

The best restaurant in town isn’t the noisy, stylish place from that guy who already has two noisy, stylish places. It’s my fancy go-to of 20 years, the one I was introduced to by an old boss. The menu has never changed, and neither has the waitstaff. I let the same waiter as always tell me about the same sides every time, oohing and ahhing like I’ve never heard of them before. We discuss at length which sides to choose, pretending we aren’t going to order them all, starting with the braised greens and the scalloped potatoes. The drinks are simple and strong. The specials are special. The seats are comfortable, and we can hear each other talk. A slick dining news website calls it “boring,” and I hear the echo, across time, of my mother saying, “Only boring people get bored.”

Dinner is only as dull as the company we choose, and this is the perfect place for a good-friend catchup. I’ve never left in under three hours, a span of time that flies. The chef pops out in her whites to see how things are going, and I hold myself back from giving her a hug, because we don’t actually know each other. One time I salute her, and she nods. But a best restaurant like this can’t be added to a seasonal roundup that will drive site engagement, by a writer with the belly of a poet, who’s just had another conversation with her editor about how nothing is the “best,” can we just say “favorite”? Can we highlight one at a time? Does it have to be a list? The editor gently reminds her that media companies require traffic, because traffic pays for writers.

We are meant to crave Burmese food on a Tuesday and see that craving through with a thorough internet search that leads us to a scrappy young woman with a pop-up.

One best restaurant is the deli counter at my supermarket, where a lady motions me over to take a look at my engagement ring, because she and her boyfriend have been dating for three years, and she’s got weddings on the brain. It’s been an utterly wretched Tuesday on my end, but I’m hurriedly buying some prepared items so we can throw together a family seder. That’s nice of you, she says, ladling out matzoh balls. “I’ll get you some of the good broth from the back. It has more veggies in it.” Her sweetness starts to smooth my frazzle, because this place prioritizes hospitality, and she’s invested in the warm reception of guests.

She asks if I’m Jewish, and I tell her I didn’t convert, but I committed. Usually I only handle our Indian stuff, but I had a little extra time and a generous impulse. We don’t stifle a generous impulse. That’s marriage, right? she asks, looking at me with eyes full of hope. And I say yes, because it can be, and grab four latkes. That night my son loves the special broth from the nice deli lady. Both kids eat their weight in buttered matzoh. I forget to serve the latkes, which I leave in our toaster oven. But I reheat them for breakfast, and they’re exquisite, even though I forgot to get applesauce. “God bless you both!” she texts, about the ring.

I think about her at the best date night spot in town, where my husband will insist on sitting down next to me instead of across from me. It makes me laugh every time, but he’s dead serious, and it’s sweet. We order a set of botanical gin cocktails and shake off our working-parent exhaustion to tune in to the delight of each other’s company. We might be caught up in a conversation about the meaning of “gyat,” the frivolous type of chat we can only get into alone, when the drinks will arrive in mismatched, delicate, vintage glassware. We look at each other—oops—and apologetically ask the friendly server if we can have them on the rocks, because we are both, unfortunately, sloshers. She takes pity.

We’re grateful to have found this friendly, intimate place on the recommendation of a friend, because no heatmap will help us plan the best route back to each other every week. And this may be because we approach our lives together as we approach all things culinary: Eating well doesn’t mean aiming for a safe bet. It means wading into uncertainty with an open heart. It means joining hands for a potentially foolish skinny-dip. Last month we spent days dissecting the absolute worst restaurant in town, a seafood place from a chef I heard interviewed on a podcast and thought might be nice for our anniversary dinner. But why did all of the fish taste like candy? we giggle. And then why was “dessert” a buttered mushroom? What would you even call the texture of the main? Fried sequins in foam, I say. We could have spent that evening, and that money, at so many other places. But exploration is about sharing whatever experience may follow: to brace for shock, to share peals of laughter, to bond.

The best restaurants in town aren’t ones that anyone else can define for us. They’re built of our memories, our heartbreaks, our highlights. The best restaurants are the ones that mean the most to us, and they won’t be spoon-fed to us in our daily media diets. They’re the ones we arrive at, physically and emotionally, on our own.